A transcript of a speech I gave yesterday for Autistic Pride! (I am absolutely terrified of public speaking, by the way, so yay for trying to overcome my fears!)

“This pandemic has seen a lot of calls for long-overdue change. At home with our thoughts, we’ve all had time to reflect on our actions and challenge existing power structures where they are vessels for systemic oppression – not just the overt kind, but also the subtle, seemingly benign misconceptions that are so deeply entrenched in us that we mightn’t even notice the damage they do to marginalised groups. The most obvious example of this is what’s happening over in the States and the courage of the Black Lives Matter Movement, but even since lockdown began, a lot of outdated behaviours have been called into question.

The five-day working week, a by-product of the Industrial Revolution we’ve now arguably outgrown. Office-based work environments, forcing people to face long commutes for jobs that can just as easily be managed remotely. Our treatment of the environment as Mother Nature thrived with some much-needed distance from her human captors.

Yes, the fundamental landscape of the world as we know it is changing and our concept of what’s “normal” is being forced to evolve, and rightly so.

For those of you who don’t know, today is actually Autistic Pride Day and for the day that’s in it, I’d like to suggest one more candidate for change – that is, our understanding of autism.

I was looking through some old school reports the other day and it got me thinking about my own journey since I was diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome, which is a form of autism, at the age of six. Just in case you think it’s all doom and gloom and we spend our lives staring vacantly into the distance while The Sound of Silence plays in the background, I’d like to share some of that journey with you today and give you an idea of how I got here today.

These report cards I just mentioned were from primary school and I was surprised to see the word “erratic” crop up repeatedly. This confused me and if I’m honest, p****ed me off as I read how this evaluation of me was contextualised. Teachers spoke of how I’d sporadically interact with my classmates for short stints and then wander off to play on my own. But erratic relative to what? Who gets to define this? As far as I could see, I wasn’t harming anyone by being perfectly content with my own company and despite my teachers’ best efforts to entrench their own values of dependency in me, I had a very developed sense of self-awareness from a young age and enjoyed an independence from the necessity of constant human company that most of my peers didn’t seem to share. From where I’m sitting, that’s not a character flaw, that’s a personal asset. An autistic asset, and I owned it. I was and still am proud of it.

Moving on to secondary school, I continued to perform well academically, but my mental health was detrimentally affected by the bullying and ostracisation I faced from my peers, partially on account of my autism and how this made me seem different, which is a terrifying thing when you’re that age and all you want to do is fit in. I did a fair bit of chopping and changing from school to school until I was lucky enough to find one whose ethos, environment and culture worked for me. During this time, there were people who were quick to write me off and had zero faith in me – someone even told my mother I’d never do a Leaving Cert and that she was being too soft on me – but as she so often is, my mother was right (if anyone here happens to know her, please don’t tell her I said that!). She knew I’d follow through, because like so many other autistic people, closure isn’t just a want for me, it’s a need and you can be damn sure that I’ll see something through to the end. No matter what obstacles I face along the way, I’d sooner realign myself and find some way to sidestep them than give up altogether. I may take the scenic route on occasion, but I always get things done and I pride myself on that.

And y’know, as soon as I found a school whose mould was flexible enough to bend to meet me and embrace me for the independent learner I am, I really thrived. At this school, there were complications with timetables and subject combinations which meant that I had to teach myself both History and German for the Leaving Cert while I’d also taken a notion and decided to take up Music as a new subject in 6th Year, which meant I had a two-year curriculum to get through in just one. Sounds like a lot, right? But strangely enough, that really felt like no biggie to me and y’know why? I had this one thing that all these other schools couldn’t or wouldn’t give me – and that thing was acceptance.

My classmates, my teachers and the whole school community saw and valued me for being my shy and yet somehow eccentric self. The me who wears baggy clothes with mismatched colours and outfits combining every season. The me who gets exhausted in crowded rooms as the conversations happening around me arrive in my ear at equal volume and I strain to filter out the voice of the person who’s talking to me. The me who could deliver a 2-hour lecture on the music of the sixties or any other subject that fascinates me, but prefers to stay quiet and listen in a casual conversation. The me who can’t always tell when someone is being sincere, but is the most fiercely loyal friend you’ll ever meet. I was me, Mel 1.0, default settings 24/7, and that was new. It was like I’d been seen for the first time and for the first time since I’d been aware what autism even was, I was happy. Not just happy in myself, but that holistic, all-encompassing kind of happy that feels so amazing and otherworldly, you wonder if it can possibly exist here on Earth and yet you dare not question it, in case you frighten it away. When you have this most basic ingredient, everything else has the space it needs to fall into place without very much effort.

I did get my Leaving Cert in the end – in fact, I got the second-highest result in the school and that same “erratic” kid those primary school reports described went on to be the well-adjusted adult sitting in front of you today. She has a GPA of 3.9/4 and is on track to graduate in August with a First Class Honours Degree in Politics, German and Irish. I quite like her and I may not always have been a good friend to her, but no matter what happens, I’ll always be mighty proud of her.

My autistic way of thinking has given me the fortitude and resolve to put the blinkers on in the face of adversity and stay the course and looking back, I wouldn’t change a single thing, least of all the moment in my late teens where I chose to embrace my autistic identity rather than see it as a source of shame. It’s been the single most meaningful moment of my life so far and I haven’t looked back ever since.

That’s the power of acceptance and it begins with understanding, which is why I think it’s imperative that the knowledge deficit around autism here in Ireland be addressed and the best way this can be achieved is through dialogue.

So dear neurotypical people: I’ve spent my life listening to you closely, trying to understand you, learning from you and even actively repressing whole parts of myself just to make you more comfortable. That’s empathy if I’ve ever seen it, even though we’re often wrongly accused of not having any. So now we ask you if you could do the same for us. Listen to our stories, learn from us and educate yourself not by TV, not by medical handbooks, but by people. Actual, living people. Warm bodies. That’s who we autistic folk really are, after all – not an -ism, not a neurology on legs, but people – a universal fact that unites all of humanity regardless of where we situate ourselves on this wonderful rainbow of identities that binds this planet together. As one of my favourite autistic advocates Jennifer Cook O’Toole says: we belong first and foremost to the human spectrum and what’s so hard to understand about that?

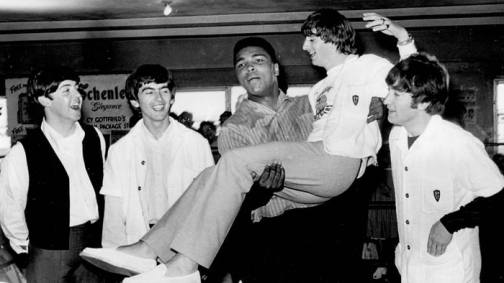

Think of everything we’ve contributed to humanity – speculation about historical figures should always be taken with a pinch of salt but nevertheless, there’s strong evidence to suggest that Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Emily Dickinson, Andy Warhol, James Joyce and countless others who’ve made invaluable contributions to humanity were all autistic. How cool is that? And that’s not just a historical trend, by the way – there are plenty of remarkable people who walk this earth today and are autistic, even if they don’t know it themselves, whether they’re household names like Bill Gates or the great many very impressive autistic people I know in my own life. But these voices are being muffled by the social stigma the autistic identity unfortunately still carries. We need a new generation of role models who are loudly and proudly autistic for autistic children to look up to as they explore their identity and choose whether to embrace it for its strengths or shun it for its challenges. In sport, in science, in business, in politics, in entertainment, in our local communities – every aspect of life stands to benefit from neurodivergent innovation. I didn’t have those role models growing up and that’s what I wish for today’s children.

Right here, right now, there’s a whole generation of young adults who were diagnosed as children and hence are the first generation to have grown up with the knowledge that they’re autistic – we’re here, ask us! You might be sitting there thinking – well, she’s nothing like my autistic nephew or my autistic colleague, but that’s exactly my point: my story is mine and mine alone but by sharing it with you, I offer you another perspective that in some ways might correspond to what you envision when you think about autism and in other ways might challenge what you think you know. By sharing my journey, the collective voice of the autistic community who’s been trying for decades to tell you we’re more than these stereotypes, that we’re not Rain Man, that we’re not unfeeling machines, that we’re diverse, that if you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism – that voice gets louder and prouder as the stigma slowly dissolves.

I know I didn’t get into great detail about what my version of autism looks like, but I can whenever, wherever. All you have to do is ask. My goal today wasn’t to give you a crash course, but to prompt a conversation. So let’s have that conversation – reach out to us, as many of us that you can find, listen to our stories, ask us your questions and open up your mind to us. We want not just to be included in this society, but also to include and the more you connect with us in your own lives, the more nuanced, well-rounded and true-to-life your concept of autism will become.

And while we’re at it, let’s change the language and stop talking about “raising awareness”. I’m aware of particle physics. Doesn’t mean I know the first thing about it. Think of other causes where we talk about awareness – Breast Cancer Awareness, MS Awareness, the list goes on. These are all awful diseases I think we can all agree the world would be better off without. But we would NOT be better off without autism – I flatly reject that idea. Autism is not a disease and yes, it is true that autistic people can and do suffer as a result of challenges they face, but by far the biggest of these challenges actually has nothing at all to do with autism itself or the people who live with it. It has to do with how a society that so poorly understand this identity reacts to us and the knock-on effects this knowledge deficit can have on our mental health. And not for a second do I believe there is malicious intent behind this lack of understanding, especially here in Ireland. I think it’s fair to say it’s not a case of not wanting to know, but it has much more to do with not knowing where to start. But why not start here?

We need to broaden our model of acceptable social behaviour to include neurodiversity and as the cloud of this pandemic slowly lifts, we couldn’t have a more optimal opportunity to sit back and reassess which parts of normal we actually want to return to.

Now’s our ideal zero-hour to move beyond performative gestures and take tangible steps to embrace neurodiversity. So let’s be brave. Let’s be curious. And above all, let’s be proud.”